As our study of Oriental rugs is to be entirely

from an Occidental standpoint, we shall first group them together without

regard to their native uses and purposes. We have found that certain shapes

and sizes are generally adhered to by Oriental weavers, and we have accommodated

in our modern homes, as best we could, that which most readily would suit

our special needs. Oblong rugs have served us fairly well as hearth-rugs

and as coverings for divans, and to throw about small rooms over a ”

filling ” of plain colour, or upon bare floors.

For room centres we have utilised the Afghan,Khiva, and Bokhara rugs, which came to us in larger sizes at first •than

other makes were apt to, and though always expensive their value has been

esteemed and considered commensurate. Long and narrow rugs we found suitable

for halls and stairs, because until of late years our halls and stairways

have been long and narrow, and have not been developed artistically.

Smooth-faced rugs, without pile (Khilim) have long been used as portieres and table-covers, and for cushions we

have utilised small saddle-bags and Anatolian mats.

Following closely upon our adaptation of things Oriental, there came to us carpets manufactured on purpose for

European and American homes, and it was then that those who could afford

to do so ordered for their large rooms and salons “Turkish,” or “Turkey carpets ” of large and heavy make.

At the same time students were beginning to investigate the manners and customs of the Orient, and to ascertain

the exact purpose for which textile fabrics were designed and made, so

that at the present time we are apt to hear names more or less correctly

applied, for in the Orient each need of life has been supplied with its

appropriate rug, and isolated facts concerning Eastern habits reveal what

many of these needs are.

However profane the use made of the Oriental rug, it was originally a thing of sentiment and should be studied as such.

With unsandalled feet the ancients stepped upon it, and the poetry and

religion of devout souls have mingled with the practical detail of daily

life to make smooth its surface of silk and wool.

- Dowry rug

- Wedding rug

- Host rug

- Hospitality rug

- Hearth rug

Each one of these was woven according to time-honoured rules, and in shapes and sizes following styles.

- Hunting rugs

- Saddle bags

- Desert and tent rugs

- Rugs for hangings and for divans

Of these many were adorned with significant

designs which indicate their uses.

- Throne rugs

- Mosque rugs

- Palls

- Prayer rugs

Aa bale containing a single specimen of each of these varieties would indeed be of inestimable value, and why should

we not be more careful in our selection of these art objects, establishing

in our minds some definite idea in making our collections ?

The dowry-rug is not always woven, but is made of material heavily embroidered or quilted in artistic design. It

is the last possession that an Oriental woman will sell, and for this

reason dowry-rugs are not commonly shown as such in this country. Small

tapestry rugs, such as are known as Kiz-Khilirn (Ghileem), or “girl-rugs

” are worked by girls, and are sometimes very beautiful.

Held to the light, a tracing in pattern of openwork is sometimes evident, and in very early weaving this pattern

was intentional, and often very intricate, not always bearing relation

to the pattern in coloured wools worked with wool upon the warp. This,

a double task, was set the weaver, and great skill marked many of these

exquisite creations.

Sometimes beads, bits of cotton cloth, or small tufts of wool, were attached to the warp threads of these Kiz-Khilims

as talismans or to keep off the evil eye. As the dread of this malevolent

influence exists universally throughout the Orient, it soon becomes apparent

to the student that many things that have worked their way into ornament

may be traced to the effort of the individual to appease some antagonistic

power and prevent evil consequences.

The charms that have proved efficacious vary, and in the most extreme cases the evil force is portrayed in animal form,

and the charm that allures the animal is adopted as a talisman. Mongolian

adherence to the effort to keep off the evil eye has very decidedly marked

the ornament of eastern Asia, and we find, even in Persian weavings, patterns

that show their origin in talismans, so that it has seemed wise to make

a special class for such ornament.

Wedding-rugs are never seen in large sizes, but all the originality and skill of the weaver was dedicated to the task

of making such a possession beautiful. In them tribal designs of significance

and purity were preserved, and they were used to cover the couch and to

screen the apartments in the home.

The new tent roof stretched, the hearth-rug finds its place. Hearth-rugs may be distinguished by the shape of the

field, which is pointed at both ends. To stand upon another’s hearth-rug

was to seek and find sanctuary. As rugs of hospitality they are indeed

well named, for we can scarce form an idea of what it meant to those whose

hands were against every man, to find a shelter from storm and from attack.

The vow of the Moslem was not lightly taken, but when it was, it was protected

by the faith which uttered the creed :

” We are believers in the book which

saith, Fulfil your covenants, if ye covenant ; For God is witness ! break

no word with men which God bath heard ; and surely He hears all ! “—Koran,

chap. xvi ; Sir Edwin Arnold, Pearls of the Faith.

In fact, of other than the Mohammedans among the peoples of the Orient the same may be said in regard to the sanctity

of hospitality. The host, whether in his home or upon his travels, was

always well equipped with textiles worked in designs that indicated their

uses.

Host-rugs for the home, showing, either in pattern or in weave divisions, where guests should sit and where the master

of the house or tent should remain ; saddle-bags and ” woven trappings,”

hunting-rugs,— and coverings of all sorts, are among the choicest

weavings to be found, and antique specimens are of great beauty.

Throne rugs and mosque rugs

Throne-rugs and mosque-rugs are naturally

the most costly and beautiful of all eastern weavings, and they demand

entirely different consideration from the rugs that are made and used

by nomad tribes and villagers.

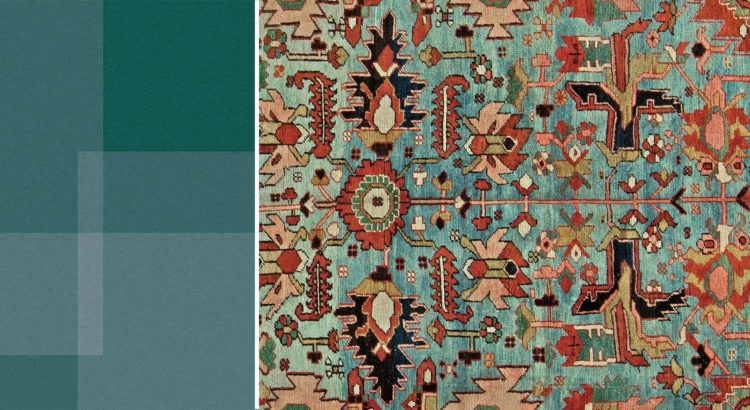

They have ordinarily been made under royal

patronage and careful surveillance, and the weavers have been protected

in every way. It has been the good fortune of wealthy Orientals to defy

the cold and unattractive winter time by having woven for them rare and

marvellous carpets, which as nearly as possible represent both the flower-strewn

fields and the gardens in which summer days and nights were spent.

Cool, splashing, and gurgling water flowing

in and about the beds of flowers in the summer gardens furnished water

motifs quite unlike those that are so called in the ornament of dwellers

on the sea-coast, where waves instead of fountains and streams inspired

brains and fingers.

The coloured tiles over which the water trickled

gave an iridescence to the transmitted hues, and lent to the ornament

derived from such natural conditions a charm that we feel in studying

the reproduction in wool of these subtle themes. Skilled workers, engaged

at the present time in the palaces and homes of dignitaries, are copying

with precision the rare carpets of past centuries, in which are treasured

up the poetry and soul of the ages.

The gardens of the Orient have marked the

art of its weavers in two entirely distinct ways. The style most prized,

if there be any definite choice, is that which in a naturalistic way portrays

minute flower forms. In palace carpets of the sixteenth century such decoration

reached its highest state of perfection, and rare copies of famous ”

palace-rugs ” are from time to time shown as museum treasures.

These are finished with narrow borders, which

serve no purpose of decoration, but merely bound the flower-strewn field.

The other style of carpet inspired by the garden is that in which the

divisions of the rug, with its borders, follow the general plans observed

in Oriental pleasure-grounds. In some cases even the crenellations that

finish the walls which surround the gardens furnish motifs of ornament

for the outside or limiting border.

The ridges that separate the flower-beds in the natural gardens are sometimes covered with vines, and these are

faithfully copied in the small dividing borders between the broad ones,

which are also ornamented with flower forms. Terraces, fountains, trees,

and fruit are all faithfully reproduced, and are treated by some weavers

conventionally, and by others in a naturalistic way.

The rose-gardens of Persia have especially appealed to the luxury-loving natives of the land loved by the poets,

for, as in all countries where desert lands abound, the oases are highly

prized, and wherever irrigation is necessary in order to make the desert

blossom, verdure depending upon human effort, man endeavours to make for

himself within prescribed limits a perfect baharistan, or paradise.

These earthly pleasure-grounds furnish to the imagination models for abodes in bliss which await those loved by

the gods, who, while resting here on earth, sing of joys to come:

” Lo, we have told you of the golden garden

Kept for the faithful, where the soil is still

Wheat-flour and musk, and camphire and fruits harden

To what delicious savour each man will.

” Upon the Tooba tree, which bends its clusters

To him that doth desire, bearing all meat ;

And of the sparkling fountains which out-lustre

Diamonds and emeralds running clear and sweet.

” Dwelling in marvellous pavilions, builded

Of hollow pearls wherethrough a great light shines,

Cooled by soft breezes, and by glad suns gilded,

On the green pillows where the blest reclines.

” A rich reward it shall be, a full payment

For life’s brief trials and sad virtue’s stress,

When friends with friends, clad all in festal raiment,

Share in deep Heaven the angel’s happiness.”

Sir Edwin Arnold,—Pearls of the Faith.

In old Mongolian devices we find, in the

outer border of garden-rugs, mountain and cloud designs indicating an

extended view from the place of retreat. These once faithfully portrayed

natural objects have very few of them been preserved with their original

meaning in modern ornament, but like scattered petals they are strewn

upon the solid-coloured fields of modern rugs in highly conventionalised

forms, as roses, tulips, pinks, and lilies.

Like throne-rugs and palace-rugs, mosque-rugs

are among the most magnificent fruits of the loom, and as votive offerings

they are made costly beyond description. Floral symbolism may be traced

in many of the designs used in these gift rugs, and panel decoration of

the most ornate character abounds which follows architectural types and

is enriched by significant motifs taken from existing ornament.

Grave rugs

In rugs that are used as palls and grave-carpets we find the tree in ornament, as well as many special emblems of mourning

that have both national and personal meaning. These fabrics are made in

all grades, needed as they are by high and low alike, and, according to

the faith of the weaver, symbols of immortality adorn them. Many of the

same general designs that are found upon grave carpets decorate antique

prayer-rugs, and the study of the ” prayer-rug ” is of paramount

interest.

When the call was first sounded in the seventh century:

” Turn whereso’er ye be, to Mecca’s stone, Thitherwards turn ! “

the necessity was forced upon the followers of the prophet to make for themselves some sacred thing upon which to

kneel. Tunics and outer garments or some woven fabrics were used, until

thought seized the inventive genius of the weavers, and its application

to warp and woof produced the prayer-rug.

The prayer rug

The field of the rug was pointed at one end,

which was supposed to be placed during the prayer so that the worshipper

should face toward Mecca, that hallowed and sacred spot where King Solomon,

more than fifteen hundred years before the birth of Mohammed, is supposed

to have gone on a pilgrimage, transported hither and thither upon his

fabulous green carpet, which at his bidding arose from the place where

it was stretched, and floated through space, covered with a canopy of

flying birds.

The necessity of facing Mecca has given distinctive patterns not only to the main outlines in the designs of prayer-rugs,

but, in detail, many of the articles used by the pious Mohammedan are sometimes worked into the fabric.

A compass was necessarily carried to determine location, so that the rug might point in the right direction. A comb to

keep in order the beard, and beads to assist in prayer, were needful accessories,

and accordingly were used in decoration. The Moslem rosary consists of

ninety-nine beads, each one designating one of the ” ninety-nine

beautiful names of Allah.”

These various articles are to be generally found in the pointed end of the prayer-rug if they are used at all in

designs. This pointed end is called the ” niche,” and it is

supposed to imitate the form of the ” Mihrab,” or niche, in

the temple at Mecca, where the Koran is kept.

” With strands of vow and shreds of prayer” have been woven, by and for the faithful, rugs which not

only bear evidence of Arabian and Turkish ideas of the needs of time,

and the belief in immortality, but designs that show that the creed of

Islam found devotees in central and eastern Asia, and even among the dwellers

in far Cathay.

Special emblems of local significance were

worked into prayer-rugs ; and Zoroastrian cypress-trees, Indian lotus-flowers,

and Chinese Buddhistic symbols testify to the mingling of beliefs.

Although prayer-rugs are now made for commercial

purposes, and vast numbers of them are sold, artistic specimens always

command our interest in no ordinary way, for there is always the possibility

that upon their surfaces some true believers in all that is good in the

teachings of Mohammed have bowed toward Mecca in response to the call

to prayer :

” Allahu!

La Ilah, illahu!”

In poetic fancy this thought has been given

expression in the verses of Miss Anne Reeve Aldrich:

My persian prayer rug.

Made smooth, some centuries ago,

By praying eastern devotees ,

Blurred by those dusky naked feet,

And somewhat worn by shuffling knees,

In Ispahan.

It lies upon my modern floor,

And no one prays there any more,

It never felt the worldly tread

Of smart bottines high and red,

In Ispahan.